The Importance of Neutral Spine

Neutral spine is a term well known and commonly used among Pilates instructors. It refers to the natural anatomical curves occurring in the spine. While we don’t necessarily live our lives in a neutral spine, when training our muscles to become stronger, it can be a very useful place to start.

Historically, Joseph Pilates (the founder of Pilates) did not teach his exercises in neutral spine. His traditional exercises demanded huge loads on the body, good coordination, good flexibility, and good joint range of movement. It was not appropriate to be used among those with musculoskeletal injuries or those who did not have the appropriate strength, coordination, flexibility, or joint range to complete them. It is for these reasons that modern-day Pilates methods, such as APPI, do not teach a lot of the traditional movements - simply because the people who are being taught do not have the prerequisites to complete the movements safely.

The spine has several curves throughout it. The neck and lower back both curve the same way: convex towards the middle of the body (lordosis). The upper back, or thoracic spine, curve is concave towards the middle of the body (kyphosis). In many cases, changes to these curves through lack of physical activity, prolonged sitting, injury, or joint disease can lead to pain and dysfunction. One of the reasons for this is because the postural muscles (transversus abdominis specifically) are no longer placed in the most appropriate length-tension for function. This is something that has been proven time and time again through research studies.

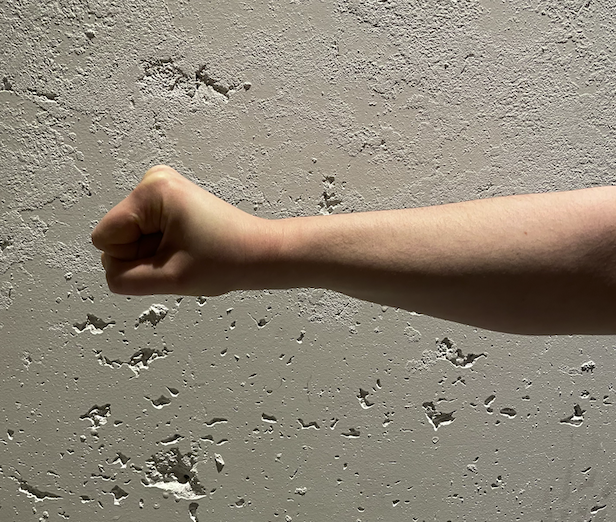

Length-tension refers to the alignment of muscle fibres (length) that determines how much force it is able to produce (tension). For instance: if you were trying to grip an object as tightly as you could, your wrist would naturally align itself in the neutral wrist position (see below).

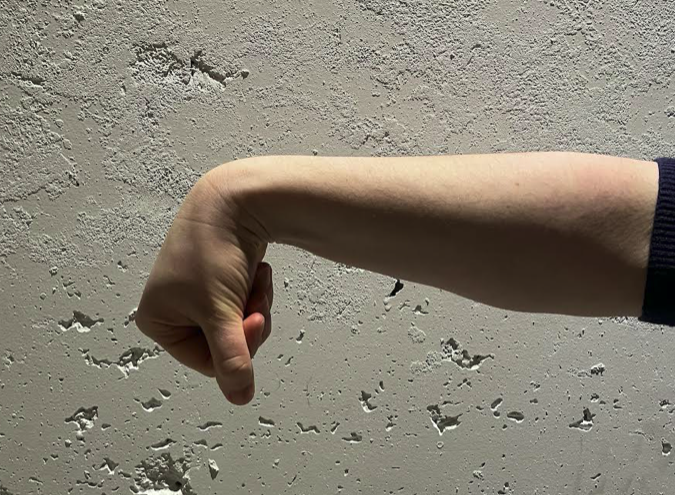

If your wrist was bent as much as it could be (see below), you would feel that it was impossible to produce the same amount of force as the neutral position. The same rules apply to the spine.

When positioning yourself in the most neutral position (neutral spine) - see below, you are able to maintain the naturally occurring curvature of your spine. This means that your postural muscles (transversus abdominis, pelvic floor, multifidus and diaphragm) will all be aligned at the most appropriate length-tension for function, which means they are able to produce the most amount of force with the least amount of effort.

If you flatten your spine (see below) or arch your back (see below), these muscles are more likely to fatigue quicker, which could put you at risk of feeling pain or injuring yourself.

Pilates is popular for those recovering from an injury or unable to complete other forms of higher impact exercise. Newcomers may not have done any other forms of exercise for many years or ever in their lives. This is why it is so important to start teaching people how to move well in the most optimal position: neutral spine. Once they have the strength and control to move out of neutral, they can do so, but doing this early may put them at risk of unnecessary injury and cause them to potentially avoid strengthening their muscles altogether.

Author: Catherine Etty - Leal (APPI course presenter/ APA titled Physiotherapist)

Refrences:

- Urquhart, D. M., Hodges, P. W., Allen, T. J., & Story, I. H. (2005). Abdominal muscle recruitment during a range of voluntary exercises. Manual therapy, 10(2), 144-153.

- Beith, I. D., Synnott, R. E., & Newman, S. A. (2001). Abdominal muscle activity during the abdominal hollowing manoeuvre in the four point kneeling and prone positions. Manual therapy, 6(2), 82-87.

- Stevens, V. K., Coorevits, P. L., Bouche, K. G., Mahieu, N. N., Vanderstraeten, G. G., & Danneels, L. A. (2007). The influence of specific training on trunk muscle recruitment patterns in healthy subjects during stabilization exercises. Manual therapy, 12(3), 271-279.